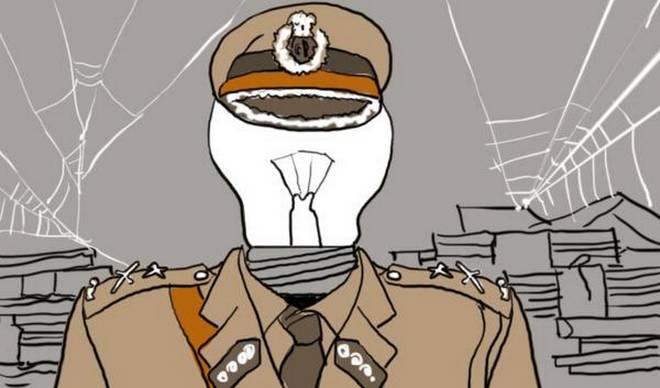

Accountability, not armour plating

Photo Credit: Deepak Harichandan

By Devika Prasad

(The Hindu)

The buzzword of police “reform” is upon us once again with the Union Cabinet approving a ₹25,000 crore outlay for upgrading the internal security apparatus in States. An umbrella scheme, ‘Modernisation of Police Forces’, has been cleared, with the government projecting this as “one of the biggest moves towards police modernisation in India”.

It is big money, especially the Centre’s contribution of about 75%, with the promise that gaps in police transport, weaponry, communications, and forensic support among others will be met. The funds are to be rolled out over the next three years, with the Centre contributing ₹18,636 crore and States₹6,424 crore along the lines of the established police “modernisation” model. Under the scheme, Jammu and Kashmir, the Northeastern States and those affected by Maoist violence are to receive special focus.

In the absence of a comprehensive policy document in the public domain that details the benchmarks of this scheme, several questions arise. It is important to cut through the hype and get to the model of reform being propagated, and be reminded of the essential reforms aimed at democratising the police which are still being firmly resisted by States and the Centre.

Facing internal challenges

This push is geared to armour plate State police in their responses to internal security challenges. Yet, with reference to Naxalism, the annual report of the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), 2016-17 notes that there has been a reduction in violent incidents and violence-related deaths since 2013. Alarmingly, there has been a 50% increase in encounters, a 122% increase in the “elimination” of armed Maoist cadres, and a larger number of arrests and arms recoveries. By its own admission, the State is killing and arresting more alleged Maoists.

It is important to point out that a Central paramilitary force, not the State police, is at the forefront against Naxal groups. With the new funds, some may argue that the police need this ‘upgrading’ in order to gradually phase out the reliance on the paramilitary. The key questions of whether further militarising of police could only increase violence, or the consideration of alternative strategies not solely reliant on coercive force, remain, unsurprisingly, absent.

There is no dent in the political discourse which accepts encounters as a legitimate crime-fighting strategy, irrespective of the strictures of the Supreme Court. Governments and the police have become glaringly opaque in their responsibility to account for deaths caused due to police action. The state needs to be reminded that it is bound to register a First Information Report and initiate a criminal investigation into any encounter killing by the police. Unaccounted deaths at the hands of the police are violations of the right to life, yet they are seen as policing dividends.

Tracking funds

Also, there are bookkeeping requirements. It may be wise to first analyse the underutilisation of existing funds in the broader context of state capacity to absorb such a significant tranche.

The 2013-14 MHA guidelines on modernisation funds mandate that every State and the Centre furnish a utilisation certificate for the full amount of modernisation funds released yearly. The Finance Ministry stresses that unless the certificates account for the full amount of funds sanctioned, no new funds will be released. Considering that only 14% of modernisation funds were spent in 2015-16, one would advise a tempering of the excitement around this infusion of funds until the previous year’s accounting is done. Not only are modernisation funds underspent, on average, but also only about 3% of Central and State Budgets are spent on policing.

Ironically, the 11th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s directives on police reform fell on September 22, and five days before this announcement. It is no secret that neither the Centre nor any State has complied with the directives in letter or spirit, with hardly any reprimand by the court itself.

Herein lies the rub; “reform” geared towards technical and infrastructural advancement is prized, but reform which squarely demands greater checks and balances is resisted and violated. Less than 10 States provide security of tenure to their police chief and key field officers. Only five States provide for independent shortlisting of candidates in the process of appointing police chiefs; everywhere else, directors general of police are handpicked by Chief Ministers. Serving police and government officers are adjudicating members on police complaints bodies even though these are supposed to be independent from the police department. “Reform” through the pathway of the directives is being mauled and distorted. This cannot be ignored in the wider discourse on police reform.

This infusion of funds could enable police organisations to overcome endemic shortages of operational resources, from transport to weapons to forensic equipment. However, the police reform to aspire for is to move beyond armour plating to accountability and the upholding of the law as measures of police effectiveness. Read more